Forgotten Old Science

Approximately 300,000 years ago, modern humans took their first steps in Africa, evolving as hunter-gatherers. It’s a fascinating journey that has led us to where we are today. However, the concept of medicines, as we understand them through the lens of science, only truly emerged in the early 1900s. In recent times, discerning consumers have made a conscious shift towards embracing organic products, distancing themselves from potentially harmful chemical concoctions.

While this shift is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, the internet is rife with misconceptions and misleading information, making it a challenge for consumers to navigate. Take, for instance, the origins of common substances like lye in soaps, which evolved from wood ashes, or the discovery of Aspirin from tree barks. Unfortunately, some unscrupulous marketers exploit the innocence of consumers, diverting them towards their products.

It’s understandable that businesses aim for success, but at what cost? Discrediting age-old scientific knowledge that has guided humanity for over 300,000 years seems not only counterintuitive but also disheartening. Our ancestors’ wisdom, rooted in traditional science, has played a pivotal role in maintaining human health throughout history.

Rather than advocating for traditional medicine, my intention is to express gratitude for the invaluable contributions of our old scientific knowledge. As we embrace new advancements in science, it’s essential to appreciate the foundations that have brought us this far—keeping us healthy and beautiful. Below, I’ve curated a list of a few noteworthy old scientific textbooks that offer a glimpse into our rich scientific heritage.

The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine (2,600 BC)

The Huangdi Neijing (given the title The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine in one of the latest translations) is an ancient treatise on health and disease said to have been written by the famous Chinese emperor Huangdi around 2600 BC. However, Huangdi is a semi-mythical figure, and the book probably dates from later, around 300 BC and may be a compilation of the writings of several authors. Whatever its origin, the book has proved influential as a reference work for practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine well into the modern era. The book takes the form of a discussion between Huangdi and his physician in which Huangdi inquires about the nature of health, disease, and treatment.

The ideas in the book have a basis in Taoist philosophy. The key to a long healthy life is to follow the Tao, the natural way of the universe. Health and illness are caused by an imbalance of the two basic forces, yin and yang, and by the influence of the five elements (water, fire, metal, wood, and earth) on the organs of the body. The organs themselves were thought to interact in ways that seem physiologically strange nowadays: the spleen “ruled” over the lungs, for example, and the lungs were connected with the skin. There was an understanding of the connection between the heart and the pulse but not in terms of circulation of the blood as understood today.

Diagnosis was mainly carried out by pulse taking, a complex process involving taking into account the time of day, season, and sex of the patient. Treatments included drugs, diet, acupuncture, and guiding the patient towards Tao.

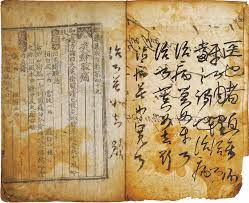

Compilation of Native Korean Prescriptions (1,443)

Korean medicine traditions originated in ancient and prehistoric times and can be traced back as far as 3000 BCE when stone and bone needles were found in North Hamgyong Province, in present-day North Korea.

Medicine flourished in the period of the Joseon. For example, the first training system of nurses was instituted under King Taejong (1400–1418), while under the reign of King Sejong the Great (1418–1450) measures were adopted to promote the development of a variety of Korean medicinal ingredients. These efforts were systematized and published in the Hyangyak Jipseongbang (향약집성방, 1433), which was completed and included 703 Korean native medicines, providing an impetus to break away from dependence on Chinese medicine. The medical encyclopaedia named Classified Collection of Medical Prescriptions (醫方類聚, 의방유취), which included many classics from traditional chinese medicine, written by Kim Ye-mong (金禮蒙, 김예몽) and other Korean official doctors from 1443 to 1445, was regarded as one of the greatest medical texts of the 15th century. It included more than 50,000 prescriptions and incorporated 153 different Korean and Chinese texts, including the Concise Prescriptions of Royal Doctors (御醫撮要方, 어의촬요방) which was written by Choi Chong-jun (崔宗峻, 최종준) in 1226. Classified Collection of Medical Prescriptions has very important research value, because it keeps the contents of many ancient Korean and Chinese medical books that had been lost for a long time.

The Compilation of Native Korean Prescriptions, (Hyangyak jipseongbang (향약집성방)), written in 1,443.

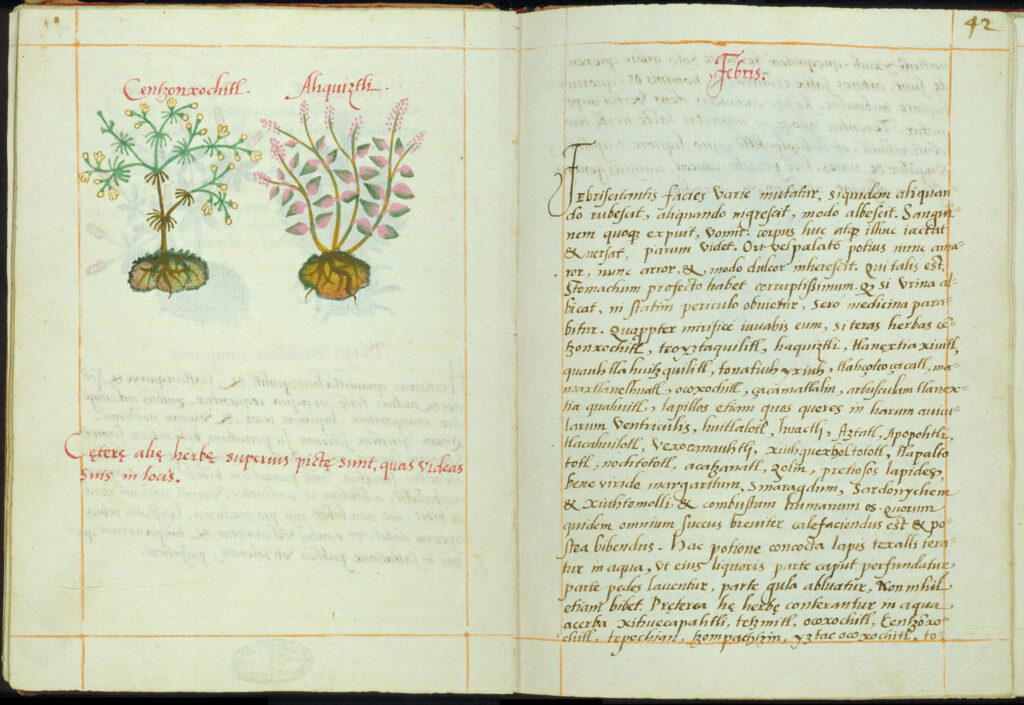

The Cruz-Badiano Codex (Translated and compiled in 1,550)

The Cruz-Badiano Codex is a jewel of a book: small, with red velvet covers and golden frames, adorned by 184 vivid illustrations of curative plants. It contains Nahua medicinal recipes compiled by Indigenous scholars of the College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, among them the physician Martín de la Cruz and the translator Juan Badiano. The book was completed in three brief months in the summer of 1552, just as the region recovered from the most devastating outbreak of the century, the cocoliztli of 1545, and the ensuing mumps outbreak of 1550.

These pages introduce a recipe for treating fever. The symptoms described likely reference cocoliztli, a lethal hemorrhagic fever that reduced the Indigenous population by approximately 80 percent in the mid-1540s: “The face of the feverish person takes on many aspects. At times it becomes red, sometimes black, and other times it becomes pallid. The patient also spits blood, vomits, the body becomes agitated and moves back and forth, vision is diminished, and the mouth senses . . . bitterness, burning, and sometimes sweetness. The stomach is very upset” (Cook 1998:101). To treat the illness, the book recommends an herbal concoction made of several plants, among them centzonxochitl (left) and ahquiztli (right).

The Dongui Bogam (Principles and Practice of Eastern Medicine) (1,610)

Known as one of the classics in the history of Eastern medicine, it was published and used in many countries including China and Japan, and remains a key reference work for the study of Eastern medicine. Its categorization and ordering of symptoms and remedies under the different human organs affected, rather than the disease itself, was a revolutionary development at that time. It contains insights that in some cases did not enter the medical knowledge of Europe until the twentieth century.[6]

Work on the Dongui Bogam started in the 29th year of King Seonjo‘s reign (1596) by the main physicians of Naeuiwon (내의원, “royal clinic”), with the objective to create a thorough compilation of traditional medicine. Main physician Heo Jun led the project but work was interrupted due to the second Japanese invasion of Korea in 1597. King Seonjo did not see the project come to fruition, but Heo Jun steadfastedly stuck to the project and finally completed the work in 1610, the 2nd year of King Gwanghaegun‘s reign.[3][7]

It “synthesized 2000 years of traditional medical knowledge” from Korea and China, and included Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian ideas.[1]